How The Trans Movement is Erasing Black Women from History

Setting the Record Straight about Pauli Murray

In the Fall of 2023, I came across a blog post that proudly referred to Pauli Murray, an iconic black female civil rights activist, and late historical figure, as a “Queer Nonbinary Ancestor”. The Author of this post consistently referred to Murray using they/them pronouns, noting that there is a newly released documentary that highlights the depth and breadth of Murray’s life, and that the film is for “god freaks, poets, and devotees to queer abundance”.

Naturally, that article led me down a rabbit hole. What was the meaning of all this? A quick Google search immediately surfaced dozens of new blog articles, academic papers, books, films, and non-profit organizations—many of whom were positioned as reliable sources—who insisted upon posthumously referring to Pauli Murray as a transgender man, and/or non-binary queer person, and referring to her using they/them, he/him, and ze/zir pronouns.

There was no speculation here. These individuals and groups insisted upon speaking for and rebranding Murray, boldly proclaiming that her most inward feelings and personal struggles were truthfully those of a black man…or otherwise—that they were unequivocally birthed from some ambiguously sexed “non-binary black person”.

It’s not often that the Woke Movement surprises me anymore, but this time, they have really outdone themselves. As a scholar of black women’s history, and as a black woman myself, I must admit that I was genuinely shocked and alarmed to see this level of erasure of our presence. And I also knew that I had to get to the bottom of this.

Because one thing is for sure: Murray never used any of these labels or pronouns to refer to herself. The word “transgender” wasn’t even in existence throughout most of Murray’s life, and the term “nonbinary”, along with its full spectrum of neo-pronouns that are now being forcibly assigned to her from the grave, have only proliferated in Western culture within the past 8 years— decades after her death.

In fact, Pauli Murray had always referred to herself as a black woman. A Negro woman to be exact, with a capital N. And her experiences and understandings of her social positioning as a Negro woman, are exactly what fueled her fierce advocacy work within the U.S. civil rights movement from the 1930s until her death in 1985. The whole point of her legacy is that she was such a powerful, dynamic force, despite the odds stacked against her due to her race and her sex. The whole point is that she advocated for both racial equality and women’s sex-based rights—for her own sake, as well as future generations.

So, what gives? Something is clearly being taken out of context. And what exactly is that thing? What is giving so many people the audacity to posthumously rewrite Pauli Murray’s history, her identity, her personal struggles, the context in which she achieved her groundbreaking work, and the community she belonged to, in order to box her into a modern-day transgender narrative?

I made a special trip to the Harvard Schlesinger Library of Women’s History, where Pauli Murray’s archives are stored, to find out. I wanted to read the same exact source material that others had hijacked.

I read Murray’s diaries, medical records, research clippings, and personal letters, to bear witness to what she said, in her own voice…without the filter of those who had so aggressively repackaged her thoughts, words, and experiences, for their own purposes.

This essay, first and foremost, sets the record straight about Pauli Murray.

It clearly demonstrates how posthumously referring to Murray as transgender, queer, or nonbinary is not only wrong and disrespectful, it is also historically inaccurate.

This piece briefly introduces Pauli Murray and speaks clearly and succinctly about her intimate struggle with gender and sexuality—focusing on the documented parts of her life journey that have led modern-day historians, academics, and activists to rewrite her as a black transgender person in American History.

I will be responding to the foremost institutions, books, and films that have forged the path of this revisionist history. As a part of my response, I will reference and share source material straight from Pauli’s archives, including letters, photos, diary entries, quotes, and newspaper clippings.

I will also be sharing my commentary on The Whys, Whats, and Hows behind it all.

Why is there such a huge incentive to reframe women’s history into transgender history? Why are our stories being so rapidly colonized?

What are the modern ideologies and dogmas we uphold about gender in this day and age? How does this inform our cultural perception of a black woman who came before our time, who didn’t believe in this ideology, despite not fitting the mold of what was expected of a woman?

Is the modern gender identity framework as progressive and inclusive as it seems, or is it just as backwards and exclusive as our past?

I will be sharing my perspective on what history teaches us about the present, and how can it help us pave a new path forward.

“One person plus a typewriter constitutes a movement”

~ Pauli Murray

A few important notes:

I have chosen to make this article free and open to the public, because I believe, amidst the rapid revisions taking place about Pauli Murray, the information and perspective I’m sharing here should be public knowledge. There is currently no other published work on Pauli Murray that offers the unique perspective and wealth of research I am bringing to the table. My intention is to make it as accessible as possible.

This project was entirely self-funded, including a little support from my loyal subscribers, and it took a significant personal investment to complete. I feel blessed and grateful that I have been able to complete this work to my heart’s content, and in accordance with my vision.

If you would like to tangibly support this work in its written form, I have made it available to purchase as an ebook on my website, which you can find here. You can have your own personal copy, with the option to download it to your e-reader for a unique and customizable reading experience, or you can print it out.

I have released an audio version of this essay for paid blog subscribers, featuring music by black lesbian songstresses of Pauli Murray’s era. You can listen here.

On March 23rd, I hosted a virtual film screening and discussion of my documentary film, Reflections Unheard: Black Women in Civil Rights. The live Q&A offered a space for my subscribers to talk about the film, as well as modern-day social issues that I touch on in this essay. You can watch a replay of our discussion here. I will be hosting more live discussions like this for my subscribers in the future. You are welcome to subscribe if you’d like to receive updates about future events and join our community.

Perspectives like mine are heavily censored. If you read this article and you learn something new, I encourage you to share a link to this blog post so that it can be well-circulated. Sharing this piece and joining the conversation with a comment can be great ways to support.

Finally, this piece is very in-depth. It’s my longest essay yet! For the best online reading experience, I suggest opening this article in the Substack web browser or app, and setting aside about an hour to sit down and read with a cup of tea.

Enjoy!

Table of Contents

Who Is Pauli Murray?

Pauli Murray’s Journey with Gender and Sexuality

The Resolution of Pauli Murray’s Gender Struggle

Was Pauli Murray Trans?

Who Is Transing Pauli Murray?

Why Are Women Like Pauli Revised as Queer or Trans in History?

Final Thoughts

Who is Pauli Murray?

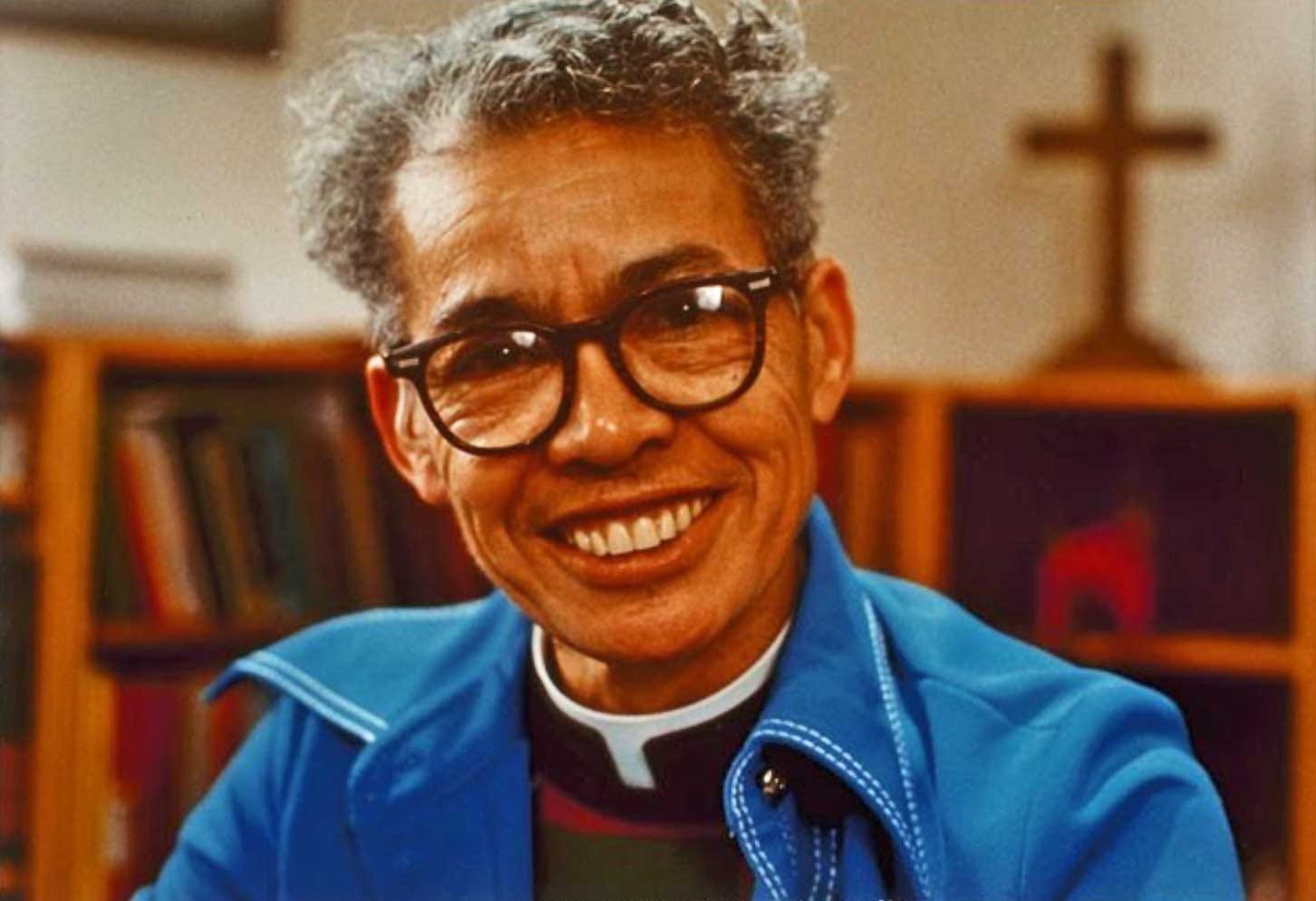

Pauli Murray was an American Civil Rights activist, Writer, Poet, legal scholar, and Episcopal Priest. Born in 1910, Murray was a trailblazer of the early 20th century, pushing boundaries for what was expected or allowed as a black woman, in both her professional and personal life.

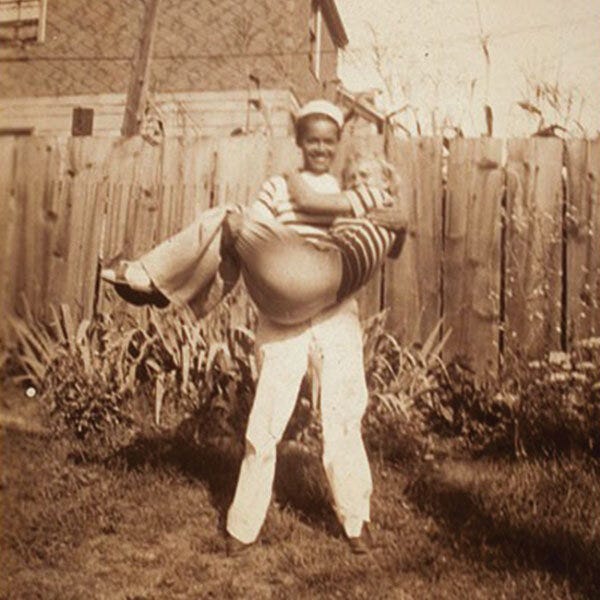

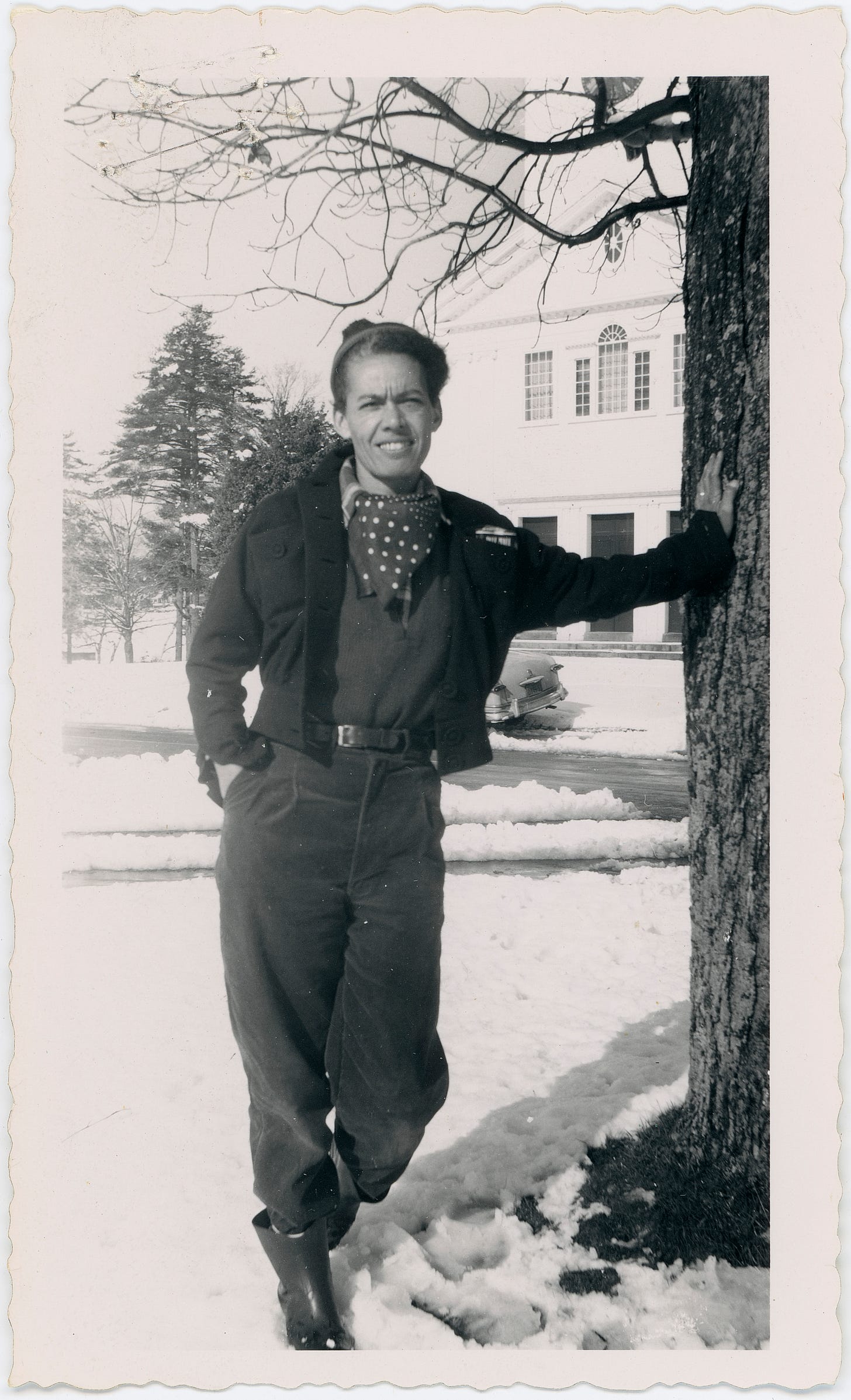

From a young age, Murray was known to herself and her family as having a more androgynous presentation and energy about her. Murray’s extensive photo archive showcases her wearing clothing typically worn by boys and young men throughout her life, aside from a few photos in her later years, where she wears a more feminine dress for certain professional activities. Pauli is also a name she chose herself; a shortened, masculinized version of her original name, Pauline. Her clothing was not prescribed to her by anyone, and her closest family seemed to accept and love her for who she was, with her guardian Aunt Pauline affectionately referring to her as a “boy-girl”. Within her own private world, Pauli’s chosen style reflected how she felt most comfortable dressing and presenting herself.

Pauli Murray’s Journey with Gender & Sexuality

In December of 1937, at age 27, Murray suffered an emotional collapse. By that point, Murray had been having severe mental health breakdowns, often resulting in a need for psychiatric attention, since she was 19 years old. The breakdowns would occur about once a year, and they were almost always linked to a failed romantic relationship with a heterosexual woman. This time was no different. Pauli had fallen in love with Peggie Holmes, a young, pretty, blonde, allegedly heterosexual woman whom she had met at Camp TERA, a New Deal resident camp to support unemployed women.

According to Jane Crow, one of the foremost biographies about Pauli Murray, Author Rosalind Rosenberg states: “Peggie loved Pauli, but she could not accept her as a man”.

It’s not stated where exactly Rosenberg’s statement about Pauli not being “accepted as a man” is sourced from. It could very well be a conclusion she came to on her own. However, it is well-documented that, throughout her young adulthood, Pauli tended to fall in love with very feminine women, who had openly affirmed their romantic preference for men.

Pauli, desiring monogamous companionship, love, and connection—was deeply traumatized by these relationships only going but so far. She repeatedly and frustratingly gave her whole heart to women who liked her, but who were deeply limited in how much they could love and fully embrace her as she was. These women were only available for serious romantic partnerships with men. She too, wanted to get married and share a life with a woman, in the way that “normal”, heterosexual people did in society.

An under-examined, yet noteworthy point is that Pauli Murray also seemed to have a penchant for white women. She was forming these romantic interests, all while exploring deeper issues pertaining to her blackness. About a year prior to meeting Peg, Pauli wrote a poem called “The Newer Cry”, a poem about her racial identity:

Let us grow strong, but never in our strength forget the weaker brother.

Let us fight, but only when we must fight. Let us work, for therein lies our salvation.

Let us conquer the soil, for therein lies our sustenance.

Let us conquer the soul, for therein lies our power. Let us march in steady unbroken beat, for therein lies our progress.

Let us never cease to laugh, to live, to love, and to grow.

In Pauli Murray’s memoir, Song In a Weary Throat, she describes a moment of vulnerability in opening up to Peg, perhaps in sharing “The Newer Cry”:

After I overcame my shyness about my writing I showed her some of my work. Peg seemed utterly without any racial or class prejudice although she was the daughter of a banker and came from conservative Putnam County, New York. When she read my poem she told me she was amazed that I could write with such compassion.

“I would be bitter if I were a Negro,” she said.

.

In my eyes, Peggie’s honest response to Pauli’s poem displayed a lack of reverence and understanding for the complexity of the African-American experience.

Perhaps Peggie was open-minded, liberalized, and not racist in a traditional sense, but that didn’t preclude her from viewing black people through a cracked lens. It would be a stretch to expect anything more from someone in her position.

Nonetheless, Pauli continued her relationship with Peg. After Camp Tera, they traveled and hitchhiked together. Pauli also made a significant effort to find a fellowship in New York while Peg was studying at Columbia University so that they could still be together after their wild bohemian adventures. Still, their relationship dissolved. There was social pressure around them being perceived as a mixed-race heterosexual couple, an imbalance between their level of access to financial opportunity—but also, most notably—Pauli was not a man.

Why did Pauli pursue relationships with women like Peggie, over women who could more readily reflect and empathize with her experience—women who could love and inspire her to be proud of who she was?

Obviously, Pauli genuinely liked these women, but that doesn’t negate the possibility that her “type” may have been influenced by colorism. Pauli grew up in an era where her race was cause for 2nd class citizenship, and that easily affects one’s sense of self-worth and perception of beauty.

Pauli also questioned at one point, why she felt “irritated” by homosexuals, instead of wanting to bond with them. To me, this sounded a lot like internalized homophobia. Although this attitude was ultimately to her own detriment, it makes sense why she didn’t seek relationships with self-affirming lesbians. It was probably too confronting.

My hunch is that Pauli upheld her preference because pretty, white, “straight”, upper-class women were upheld as the model of beauty, womanhood, and desirability. She too, was a product of her environment, shackled and deeply influenced by cultural norms.

Being a masculine-presenting woman whose “greatest attractions” were to “extremely feminine, heterosexual” women, Pauli did not neatly fit into the societally prescribed model of who such women belonged with. Pauli had no true reference for who and what she was, or who she loved. She didn’t identify as a lesbian, and the women whom she loved didn’t want her the way she was. They wanted a man. Also, in her professional life, particularly during her boundary-breaking stints pursuing higher education, Pauli was often surrounded by either the white elite or black men. She was in a class of her own, usually the only one of her kind.

Pauli had no community or visibility for women like her, and no models of what a healthy, happy lesbian relationship could look like. With her unresolved mental health struggles looming amidst numerous other social and economic pressures, Pauli began to question why she was the way she was, seeking answers, and becoming desperate for a final resolution to put an end to her suffering.

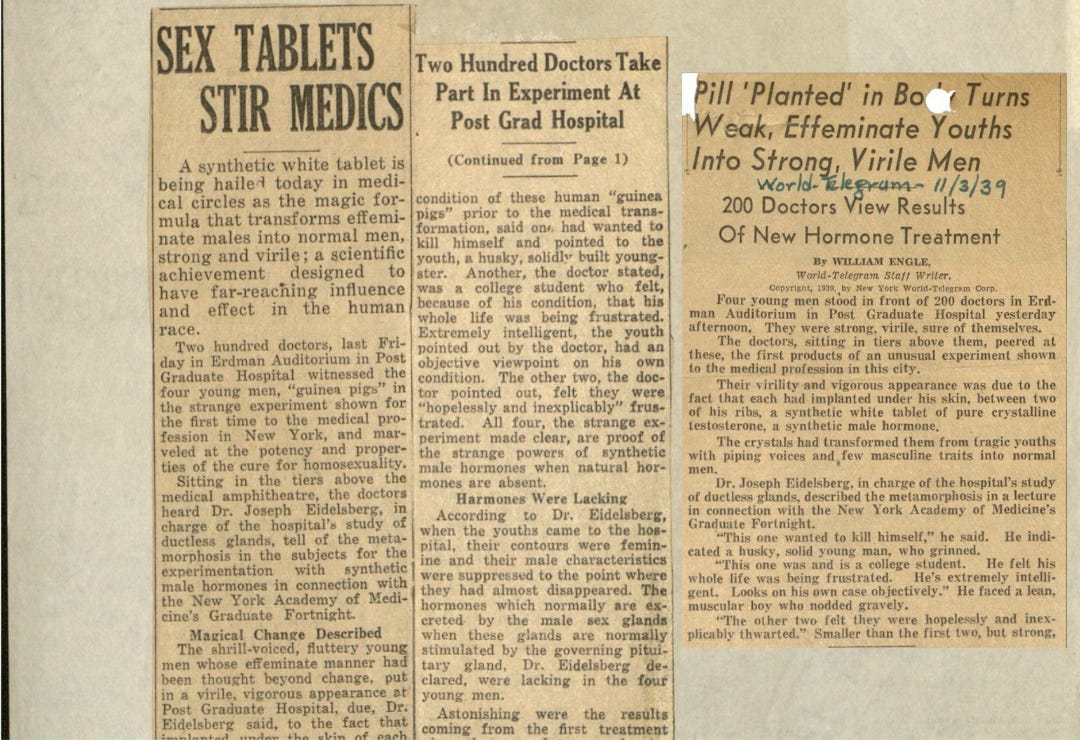

In November 1939, Pauli came across two newspaper articles, each of them advertising the new release of testosterone pills to aid in the masculinization of effeminate men. The New York Amsterdam News article was titled, “Sex Tablets Stir Medics”. The article states:

A synthetic white tablet is being hailed today in medical circles as the magic formula that transforms effeminate gay males into normal men, strong and virile; a scientific achievement designed to have far-reaching influence and effect in the human race…

[Two] hundred doctors, last Friday in Erdman Auditorium in Post Graduate Hospital witnessed the four young men, “guinea pigs” in the strange experiment shown for the first time to the medical profession in New York, and marveled at the potency and propensities of the cure for homosexuality.

Another article from the World-Telegram interviewed Dr. Joseph Eidelsberg, who proudly shared the “success” of the experimental procedure on his patients. He is quoted:

“This one (male patient) wanted to kill himself,” he said. He indicated a husky, solid young man, who grinned.

In reading these articles, Pauli did not hesitate to act on what she saw as an opportunity to alleviate her struggle. Two days after the release of these news clippings, she wrote a letter to Dr. Eidelsberg, asking for an appointment for more information. She also wrote Dr. Charles Richards, her own doctor, asking him to refer her to Dr. Eidelsberg for an appointment.

In her letter to Dr. Richards, Pauli expressed a sense of urgency around getting the treatment she so desired, as her mental health waned. She wrote:

“I need your aid. My problem has become increasingly more difficult during the past year, and the fall and winter months are most troublesome to get through.”

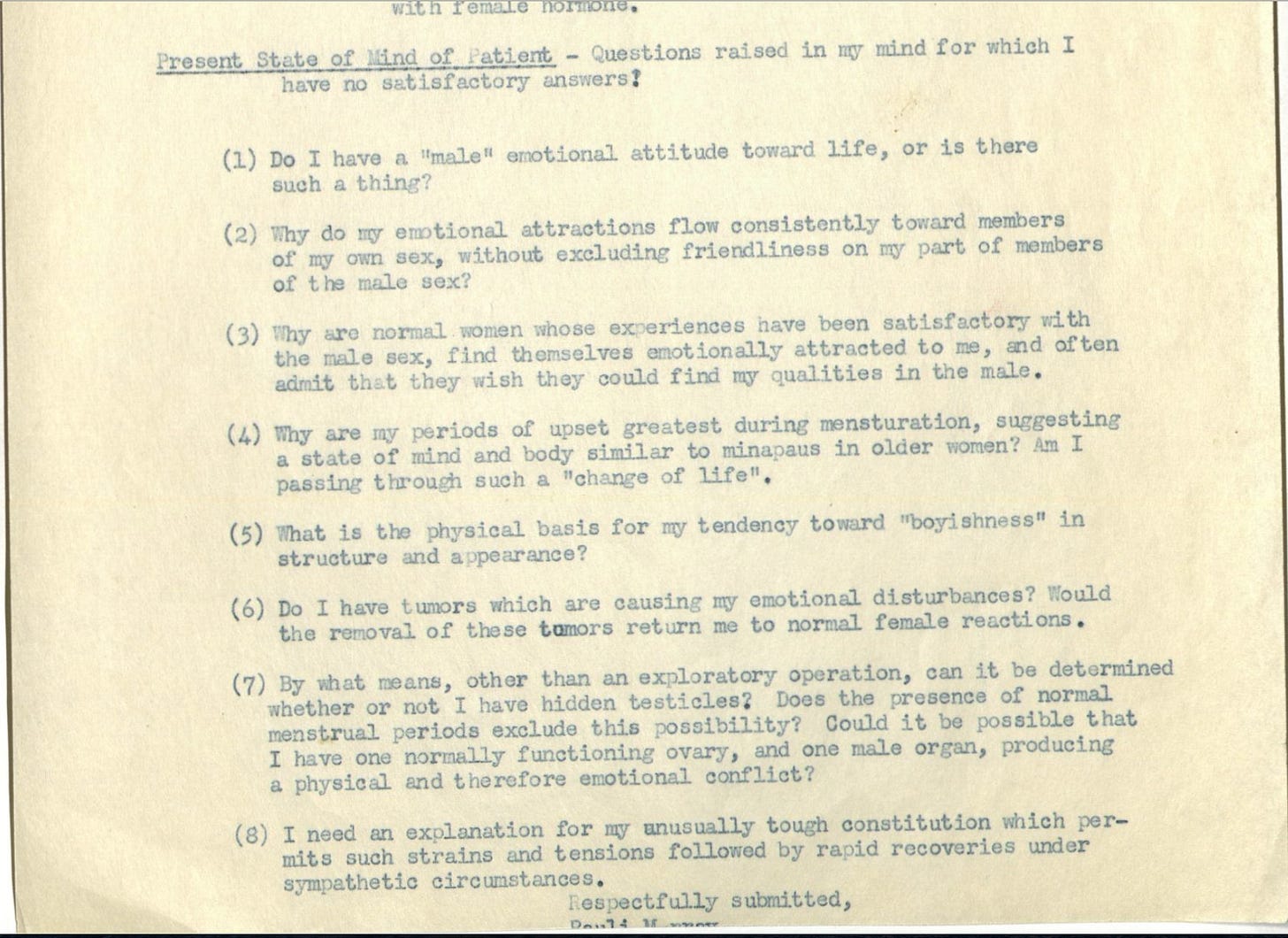

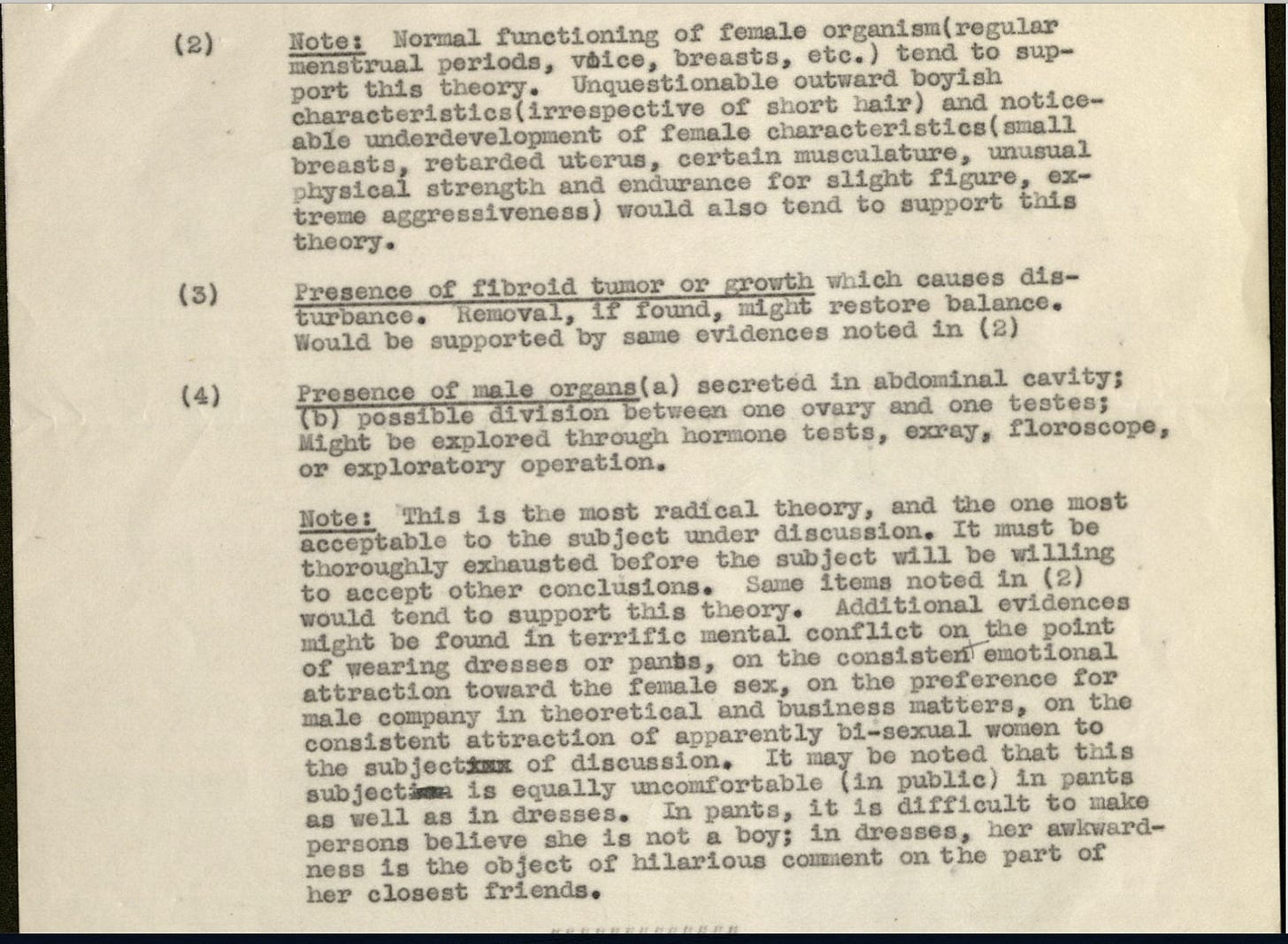

In March of 1940, Pauli suffered another mental collapse, and was admitted into the Long Island Rest Home, a Psychiatric Institution in New York. It was during her hospitalization when she began a very extensive self-evaluation, which she openly shared with doctors as a part of her request for experimental testosterone pills.

It is in Pauli’s notes to herself and her doctors that reveal her deep struggle with her sexuality, the questioning of her gender, and her quest to find out the truth of who and what she is. And I believe that these notes form the crux of what has been used to rebrand Pauli as transgender.

In Murray’s “summary of symptoms of upset” she included lists of questions she had been seeking answers for, and was hoping to find relief within the medical sphere.

“Do I have a ‘male’ attitude towards life, or is there such a thing?”

“Why the very nervous excitable condition all my life and the very natural falling in love with the female sex? Terrific breakdowns after each love affair that has become unsuccessful?”

“Why do my emotional attractions flow consistently toward members of my own sex, without excluding friendliness on my part of members of the male sex?”

“Why cannot I accept the homosexual method of sex expression, but insist on the normal first?”

“Why are normal women whose experiences have been satisfactory with the male sex, find themselves emotionally attracted to me, and often admit that they wish they could find my qualities in the male.”

“What is the physical basis for my tendency toward ‘boyishness’ in structure and appearance?

“Do I have tumors which are causing my emotional disturbances? Would the removal of these tumors return me to normal female reactions.”

“By what means, other than an exploratory operation, can it be determined whether or not I have hidden testicles? ….[Could] it be possible that I have one normally functioning ovary, and one male organ, producing a physical and therefore emotional conflict?”

Pauli carried a strong sense of urgency around her self-inquiry, creating memorandums using the information she had gathered, and sharing it with her physicians. Clearly, she saw testosterone as a potential light at the end of a very dark tunnel, and was unabashedly clear that she was willing to lay down and be experimented upon.

In 1942, Pauli discovered Dr. Ruth Fox, another physician who was carrying out similar trials with testosterone. They were both scheduled to be at Martha’s Vineyard at the same time in the summer, so Pauli wanted to take that opportunity to receive hormone therapy. Pauli was very clear that testosterone was an experimental drug, and she was ready and willing to be their guinea pig. Within her letter, she wrote Dr. Fox:

“Are you still experimenting with hormones?…[If] you were interested, I could make myself at your disposal for two weeks….

I do hope you’re in an experimental mood. Let me know at once, won’t you.”

The aspect I find most interesting about Pauli’s self-inquiry is that it was all rooted in biology. Even though she had internalized gender stereotypes, she still didn’t jump the gun to identify as a man, even though at some point, she truly desired to become one—because she still knew that gender was rooted in biological sex. This is an important distinction, since modern-day transgenderism is actually based on personal identity, regardless of the reality of biological sex.

She was genuinely speculating as to whether or not she was actually a biological male, or some form of “hermaphrodite” as she put it, based on her homosexual attractions and gender nonconformity. Pauli largely thought of her problem as being “glandular”. If there was in fact, a tumor that needed to be removed to return her to “normal female reactions”, she wanted it to be removed.

Given the times, it makes sense. Pauli had no language, visibility, or community for women like herself. In observing her own attractions and behaviors, the closest and most accessible mirror that Pauli could find was the image of a man, so she wanted to double-check if she was one.

And if her theory about having male organs was true, she wanted to experiment with testosterone so that she could masculinize herself further, in order to alleviate her homosexuality and androgyny—the perceived sources of her pain. This was exactly what the drug trial promised.

On top of the array of mental health issues stemming from her homosexuality, Pauli was also dealing with economic pressures, and the daily oppression of being a black woman during her time.

It’s noteworthy to mention that Pauli was rejected from several major Universities solely due to her sex, including Harvard University.

Aside from easing more intimate matters, could becoming a man possibly open doors to greater opportunity? Historically, several women have posed as men for this very reason.

When Pauli was initially rejected from Harvard University on the basis of her sex in 1944, she appealed, half-jokingly stating that she would “gladly change her sex” to be admitted, but simply cannot figure out the means to do so at this time. She eventually was admitted as a woman, after years of advocacy.

Given these various factors of what we know about Pauli’s longstanding struggle with her homosexuality, racial and gender discrimination, and the mental health issues it directly caused, I think it’s reasonable to conclude that her search for testosterone was a trauma response.

In observing what society deemed appropriate for men and women, and considering gender stereotypes, it makes sense that Pauli identified more with the male archetype. It also makes sense that she wanted to figure out which “box” she fit into, and understand the tangible differences that she saw between herself and the women around her. She saw a possibility within this experimental drug that could help her self-actualize, and ultimately ease her navigability through life.

To this day, it’s very hard to be a gender nonconforming lesbian. Even with our hard-won civil rights in the U.S.—community resources and visibility that center the lesbian experience are severely lacking, especially in a culture that erases them.

Pauli’s story parallels that of so many gender nonconforming people of today, who find themselves between a rock and a hard place, feeling social pressure to “transition” to appear as the opposite sex, instead of being supported in living, loving, and existing as they naturally are, without a need to change their identity, pronouns, or bodies.

I find it interesting that the testosterone pills which Pauli was so fervently pursuing, were openly and unapologetically intended to be used as conversion therapy on gay, effeminate males. I also do not think it’s a coincidence that Pauli struggled with her own homosexuality, and saw this pill as an antidote to her same-sex attractions.

What’s more, modern-day hormone therapy has been shown to have the same effect on its users, as far as changing their sexual orientation. It continues to baffle me that cross-sex hormones for ‘gender-affirmation’ are still viewed as progressive. I think we can all glimpse into the history of experimental hormone usage as a means to change one’s “gender expression” and examine the roots of where it comes from.

Given what we know about the factors that prompted Murray to seek testosterone, is this really something that we should celebrate and glorify?

The Resolution of Pauli Murray’s Gender Struggle

At the height of Murray’s quest for testosterone and further medical evaluation, she corresponded with various doctors, outlining her symptoms, characteristics, and theories about what was wrong with her.

Upon submitting a Memorandum with a summary of her symptoms, she noted her own “radical theory” that she has male organs. This theory was solely on the basis that she is same-sex attracted, and equally uncomfortable wearing pants as she is wearing dresses (in public) because her androgyny makes it difficult for others to read her properly. This theory that she possibly has male organs, she said, must be “thoroughly exhausted” before she is willing to accept other conclusions.

However, the doctors she wrote to, assured her that there was no biological basis for her concerns.

Dr. Eidelsberg wrote to Pauli,

“I am sorry, but medical science is not entirely keeping with your conclusions. We will gladly do what we can with you and your problem, and make an exhaustive study to determine if there is a glandular disorder, and treat it if such can be found.”

Dr. Ruth Fox wrote her too:

“You know that I believe it [your problem] is a psychological matter, but any of us would be glad to find a physical basis for your trouble and I am heartily in favor of your having the tests.”

Pauli’s records also show a letter from what appeared to be a friend. It was a deeply personal, honest, and richly handwritten letter in script, encouraging Murray to accept herself as she was. She wrote,

“I would like to speak with you at length on the declaration, if it is a declaration, which you have made as to your future enterprises. Personally, I do not think it is such a good idea. Although few people are willing to accept this fact, there definitely are three classes of human beings; the true man, the true woman, and the homosexual. If you have tendencies to swerve toward the third class, then that is where you belong. Why try to change yourself?”

The letter was signed “with love”, and a flourish of the hand as a signature, so it’s difficult to confirm who it was from, but the associated envelope stated that it was from Dorothy Schultz, a colleague of Murray’s. Although I disagree with the description of homosexuals as a separate class from true men and women, I think it’s noteworthy that she loved and accepted Murray as she was, and encouraged her to do the same.

The core essence of this letter was to discourage Murray from attempting to be something that she was not and accept herself for the sake of aligning with Pauli’s stated values on personal freedom. This letter truly stood out to me, so I have published a separate piece transcribing it and sharing further thoughts.

I also think it’s noteworthy to add that Murray’s doctors were not negligent. They never expressed any prejudice against her for being homosexual, or for wanting testosterone: they all responded to her inquiries, carried out her desired tests for any glandular issues, suggested that this was a psychological issue, and simply didn’t entertain her request to be experimented on.

The medical records that documented Pauli’s gender struggle spanned from 1939-1944, and then there was nothing after that. We don’t exactly know how or when she reached an inner resolve, but we do know that she never actually took the testosterone, and she never actually “transitioned” into life as a male, socially or medically.

We also see that she clearly and openly identified as a woman later on in life, ultimately strengthening her feminist values around women’s rights, and tying them into her racial advocacy work, as well as her work as an Episcopal Priest.

Murray saved numerous clippings she found interesting, including articles, brochures, and flyers from events she attended and was invited to, as well as her own writings. Within them, she would highlight sentences and paragraphs that stood out to her most.

Her archives show that in the years following her quest for hormones, she studied and explored various topics ranging from female sex stereotypes to homosexuality, to black women’s liberation, to feminist theology. All of her readings enriched and informed her writing. Pauli eventually published a very strong article called Minority Women and Feminist Spirituality in her later years.

Pauli also seemed to find some healing and community through her Writer’s residency at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire, which she attended to write her genealogy memoir, “Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family”. In November of 1955, Pauli wrote a glowing letter to Mrs. Macdowell, the owner of the estate, sharing her experience of being present on the grounds:

“In every stone, pebble, tree, bush and structure of MacDowell, your love and care has gone into the making of it - - and I find this place one of greatest healing in my sorrow.”

It was also at the MacDowell Colony that Pauli formed a close friendship with Helene Hanff, a fellow resident and aspiring playwright, whom Pauli playfully referred to as “Butch”. Helene was a same-sex attracted woman who seemed to be fairly comfortable with her sexuality—but like Pauli, she also did not label herself as a lesbian. Pauli and Helene wrote to each other often, offering each other laughs, insights, and moral support on each other’s personal lives and creative projects. In one letter Pauli wrote to Helene about her time at the MacDowell Colony, she shares a profound insight on what it has meant for her to find a home where she truly belongs:

You must remember, Helene, that we who feel this deep gratitude are the unestablished, the unrecognized, unfulfilled-so-to-speak “artists” who do not dare call ourselves “artists.” For so long we have been homeless, wandering, square pegs-in-round holes, unable to hold steady jobs and be solid citizens, carrying a load of guilt that we don’t function like other people-get married, have children, go to Europe, give big parties, etc. etc. — that to find a place where our “queerness” is normal, where our bodies and souls are considered precious, a feeling which seems to infect the entire personnel — naturally we would have this common reaction.

Those who have had some recognition, some successful reviews or plays or compositions, etc., etc., may not have the humility that precedes success. Our job is to remember that should we ever be successful, we never lose this childlike wonderment at life and people.

.

In seeing the transformation in attitude and disposition over the course of Pauli’s life, I think it is safe to say that she was able to access greater peace and resolution, while fully embodied within herself as a woman. She achieved this without having to move forward with her earlier plan to experiment with testosterone, which she fervently undertook in the midst of a mental health crisis around her homosexuality.

Some people might say that Pauli had no choice because she wasn’t offered access to testosterone, and because the doctors she pleaded with did not bow to her sense of urgency to be experimented on. But it’s noteworthy to mention that she was able to access that inner peace nonetheless, through natural means. And it’s best that she did, since we now know that testosterone is a harsh drug that often causes serious medical complications in females.

With Pauli’s personal evolution and healing through like-spirited community, exposure to expansive perspectives on womanhood, and maturation into her own life purpose, came a natural cessation of her fervent quest to find a home within herself as a man. By the end of her life, Pauli had come a long way, growing into herself as a woman, walking in her purpose, in all of her uniqueness.

Was Pauli Murray Trans?

Now that we have a picture of Pauli Murray’s journey with gender and sexuality, let’s ask the question:

Was Pauli Murray Trans?

If so, what exactly makes her transgender? When we break down that question, we have to ask, What defines someone as trans to begin with?

In the mid-20th century, the term “transsexual” was coined. The definition of a transsexual was very clear and simple: It refers to a person (most commonly a male) who has undergone “gender-reassignment surgery”, a form of plastic surgery that attempts to change the appearance of one’s visible sexual organs to appear more like that of the opposite sex.

However, Pauli Murray underwent no such surgery, and she did not even take hormones. So, she does not fit this definition.

In modern times, however, there has been a push to redefine “Trans”, such that it is not dependent on whether or not someone undergoes any surgeries or medical procedures. As of right now, there is no standard, clear, or widely agreed-upon definition of “Transgender”. In fact, anyone can identify as Transgender or Non-Binary, and be socially affirmed as such if they so choose, no matter how they look or behave. Thousands of people slip in and out of the trans identity over time, for various reasons.

Our modern definition of “Trans” is therefore entirely based on whether or not someone personally identifies as trans, and nothing else. There is no such thing as someone being inherently transgender.

Trans identity is based on one’s relationship to gender as a concept, which is largely based on Western, Eurocentric gender stereotypes, sprinkled with New Age Philosophies. Here, Manhood and Womanhood are conceptualized as spiritual feelings, rather than biological states of being.

However, Pauli Murray does not fit this definition of transgender either, since:

a. She never identified as transgender, transsexual, or non-binary.

b. She never identified as a man, either publicly or privately.

c. She speculated as to whether she was actually biologically male or intersex based on her homosexual behavior, and later confirmed that she was not.

Noting the last point, the genuine speculation Pauli had about the true nature of her biology due to how well she fit into male gender stereotypes, is not the same thing as affirming the idea she is indeed male or intersex based on a metaphysical claim of being “born in the wrong body”.

…nor is the same as simply choosing to identify outside of womanhood, with full knowledge and awareness of her female biology, and then attempting to live in society in the way that she perceives herself to be.

The latter two examples are hallmarks of modern-day transgenderism, and she fits neither.

But if people truly wanted to rest on the notion that Pauli Murray was trans, they would also have to acknowledge that she was a “desister”. A “desister” is a person who socially transitions, identifying as transgender or nonbinary without medical intervention, and later returns to identifying with their biological sex.

But no case has ever been made that Pauli Murray was a desisted woman, because it seems that most sources who claim that she was transgender, want to erase or gloss over the fact that she eventually settled into her womanhood after all. Also, the term “desister” doesn’t accurately apply here, since Pauli Murray never socially transitioned, or identified as Trans in the first place.

The fact is, she was questioning her biological sex. She was a woman, and she also identified as such. That ought to be respected, without putting words in her mouth.

Finally, some people define Murray as transgender by saying that she experienced “gender dysphoria”, a condition that implies dissatisfaction with one’s biological sex—which also implies that anyone who experiences gender dysphoria is transgender. This is faulty for a few reasons.

First of all, the term gender dysphoria was coined in 1977 by psychiatrist Norman M. Fisk. This was just a few years before Pauli’s death, long after she had already embraced life as a woman. Pauli underwent rigorous psychiatric tests and hospitalization in her youth, and was never diagnosed with gender dysphoria or anything like it, despite having doctors who cared about her. We literally have her medical records to prove it!

But if we, as everyday people, have the gall to posthumously diagnose Pauli Murray with gender dysphoria, let’s at least consider the following:

Gender Dysphoria is a socially engineered condition. No one knows what causes it, it was only recently made up within the last 50 years, and the concept of it is entirely based on Western gender stereotypes and cultural attitudes.

What exactly does it mean to feel like you are the opposite sex? Is womanhood a feeling?

Based on this logic, a tomboy might develop ‘gender dysphoria’ if she is made to feel ashamed or ostracized for wearing the clothing she likes, liking girls, or participating in traditionally masculine activities. But where do we get these ideals from? Where do we get the idea that gender non-conformity is wrong?

Our culture.

In other cultures where these norms do not exist, you will not find a proliferation of gender dysphoria. There is no evidence that gender dysphoria is culturally universal, or that babies are born with it. Much like anorexia, certain psychological conditions are Western-bound syndromes that are developed entirely through lived experience.

Another noteworthy fact about gender dysphoria is that it is often onset by trauma or social contagion. Studies also show that the vast majority of children who are diagnosed with gender dysphoria outgrow the condition. I think due to these factors alone, it’s inappropriate for anyone (including doctors) to label someone as “trans” just because they may be diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

Also, it is extremely common for people to experience some form of discomfort with their biological sex at some point in their life.

We live in a society that offers us degraded and boxed-in examples of who we ought to be as girls, boys, women, and men. For many girls and women, this is further compounded by safety issues and sexualization. For bi and lesbian women, it is even further compounded by not fitting into gender stereotypes in very prominent ways. While some of us suffer from this discomfort more than others, these feelings are not exclusive to those who identify as transgender.

It’s important to not jump the gun and slap a “trans” label on someone just because they may have experienced said “dysphoria” at some point in their life. There are many reasons as to why someone can feel uncomfortable within their own body, and that should be explored for what it is.

While the psychological struggles people go through are very real, Gender Dysphoria as a diagnosis is a very abstract, broadly defined, newly made-up diagnosis—and it should be taken with a grain of salt.

It’s definitely not something that we should feel at liberty to posthumously apply to someone who died long before the term was created, and use as justification to rewrite their entire history.

Who Is Transing Pauli Murray?

Some very notable sources have rebranded Pauli Murray as transgender, from books to films, to academic articles. However, I’ve found that the platforms that have been the most adamant about narrating Pauli Murray as a trans historical figure, are also some of the most highly influential and integral resources we have about her: those who have taken on the huge responsibility to preserve and amplify Murray’s history to the public.

Amongst them include The Pauli Murray Center, an education center and significant history site, anchored at Pauli Murray’s childhood and family home in North Carolina.

On the Pauli Murray Center’s official website, there is an entire page devoted to Pauli Murray’s “Pronouns”, where the Center attempts to educate the public about various neo-pronouns, and how they’ve chosen to reference Pauli Murray. Here is what they have to say:

“We don’t know how Pauli Murray would identify if they were living today or which pronouns Murray would use for self-expression.

Murray self-described as a “he/she personality” in correspondence with family members. For years, Murray requested - and was denied - testosterone injections and hormone therapy, as well as exploratory surgery to investigate their reproductive organs, believing that they may have been intersex and had undescended testis. Later in journals, essays, letters and autobiographical works, Murray employed “she/her/hers'' pronouns and self-described as a woman.”

Currently, the Pauli Murray Center chooses to use he/him and they/them pronouns when discussing Pauli Murray’s early life and she/her/hers when discussing Dr. Murray’s later years. When discussing Pauli Murray in general, we interchangeably use she/her/hers, he/him/his, and they/them/theirs pronouns, or we refer to Pauli Murray by their name and title(s). We hope this strategy will encourage readers to embrace the individual and fluid nature of gender.”

I find it very disconcerting that the Pauli Murray Center has admitted that they don’t know how Murray would have identified today, but they still chose to make an executive decision to refer to her using alternative pronouns rather than how she referred to herself.

I also find it concerning that they/them pronouns are seemingly being used as “gender-neutral” pronouns, even though “they” is far from neutral, even in this case.

Pauli’s records do not show that she ever publicly or privately used he/him or any other pronouns for herself—even during her questioning period when she expressed interest in taking testosterone, and even with her playful self-description of having a “he-she” personality. Pauli also unwaveringly identified as a woman by the end of her life.

For the record, I think it’s incredibly patronizing to believe that posthumously changing Pauli Murray’s pronouns is the “respectful” thing to do, under the supposed guise that she simply didn’t have that language to refer to herself in the way she might today.

Pauli Murray, although shackled by oppression for much of her life, was a poet, and a brilliant, highly educated writer who was gifted with words. If she wanted to directly refer to herself as a he/him or they/them even if it were just imaginatively within her personal diaries, poems, or letters to loved ones, I’m sure she could have done as much.

But she didn’t.

There is clearly a double standard here, which favors trans identity over womanhood.

Pauli Murray went through a period of questioning her biological sex and later settled into her truth of being a woman, and it is not taken as a realization of who and what she always was. Nobody took her open, clear proclamation of womanhood after her struggle, and ran with that.

But when actual trans-identifying people claim that they were later bloomers, that they “discovered” themselves as being born in the wrong body, or that they were always truly the opposite sex, woke-liberal folks always respect these claims as proof that these people came to a major realization as to who they always were, from childhood. They unquestioningly affirm it.

Instead, it is implied here, that she simply “decided” to be a woman or that she fluidly “flowed” into womanhood, later in life.

So in some cases, Transness is seen as being fixed and innate—and in other cases, it’s seen as fluid. That’s because there is no standard concept or definition of being trans. It is whatever people want it to be, when they want it to be that thing. I suppose this is convenient when you’re revising history.

In this case, the Pauli Murray Center claimed that they were celebrating the ‘fluidity of gender’, because that’s their weak justification for using a confusing array of pronouns to posthumously reference Murray in her various stages of life, without her consent.

The information that we do have on how she identified is not taken as it is, simply because it doesn’t suit some people’s narrative of who they want her to be.

Pauli Murray’s autobiography, “Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage” was posthumously published in 1987, just two years after her death. In her memoir, she never mentioned anything about her quest for hormones, identification with maleness, or homosexuality. She talked about her androgyny, how she liked to dress, and how others perceived her—but she didn’t discuss the deeper elements that were later discovered in her medical records, letters, and diaries.

Perhaps, she didn’t want to talk about that aspect of her life because it was too private, or she didn’t want to be remembered that way, or it was no longer important to her. Pauli spoke of herself and her life’s work as a Negro woman. She said her greatest accomplishment as a Negro woman in America, was that she survived. This was her final word about herself, and the legacy she wanted to leave for the world.

The original introduction to Pauli’s autobiography was written by Eleanor Holmes Norton, a mentee of Pauli’s—someone who had worked closely with her. At the end of Eleanor’s glowingly rich account of Pauli’s life and legacy as a black woman trailblazer, she writes,

“Characteristically, Pauli has had the last word on herself.”

But in 2018, a new version of “Song in a Weary Throat” was published. Nothing in the book was changed, except for a new Introduction by Patricia Bell Scott, and a new summary of the memoir, which is printed on the dust jacket. Immediately upon opening the book, the inner flap includes a blurb about Pauli Murray’s alleged transgenderism:

“In fact, throughout her life, Murray would struggle with feelings of sexual ‘in-betweenness’—she tried unsuccessfully to get her doctors to give her testosterone—that today we would recognize as a transgender identity.”

How ironic. It seems Pauli Murray hasn’t had the last word after all.

What is the use of stating how “we” would recognize Pauli Murray as transgender? Who exactly does “we” speak for? Clearly, not everyone. This assumes that everyone in our society would or should unquestioningly view Pauli Murray as transgender.

It also re-contextualizes her entire life, rather than focusing on the reality of her relationship with herself and the society she lived in during her time.

Also, for many people who inject a transgender identity into Pauli Murray’s narrative, their justification is that she might have identified herself as a transgender man today, but she didn’t have the language or acceptance at the time.

They use this idea as a means to label Pauli as trans or to radically emphasize “Non-Binary” as a consummate description of her gender and sexuality, without even mentioning her homosexuality.

But if we want to play with our imagination, it’s just as easy for someone like me to dream up a story, and say that Pauli Murray would have not only identified as a woman, but also fervently disagreed with the modern-day trans movement because it completely negates the reality of biological sex—something that played a huge role in her activist work, and her life struggles.

I could easily reframe her advocacy to rewrite her as a “black radical feminist”, and say that she would have identified as a “black butch lesbian” if she had the ‘language and awareness’ of our modern times.

But, I don’t do that, because I would be projecting my imaginary narrative onto her and rewriting it as truth.

It’s disrespectful.

And in any case, women who think like myself are not positioned with the institutional power and resources to completely rewrite Pauli Murray’s history. So it doesn’t matter if there are other imaginations and perspectives on who she could have been today. The trans narrative is privileged over all others, and that’s what is depicted in history books and taught in schools.

The truth is, we will never really know how Pauli Murray would have interpreted or identified with modern language and events. We only know how she actually did identify, and what she did and did not do. That should be enough.

My Name is Pauli Murray, is an award-winning documentary detailing Pauli Murray’s life and legacy that was released by Amazon Studios in 2021. As this film is the only major movie that’s been produced about Pauli Murray, it currently occupies a position as being the most mainstream and visible audiovisual educational resource about her life, to date.

The synopsis of the film affirmatively refers to Pauli as a non-binary person, with they/them pronouns:

“Overlooked by history, Pauli Murray was a legal trailblazer whose ideas influenced RBG’s fight for gender equality and Thurgood Marshall’s civil rights arguments. This is a portrait of their impact as a non-binary Black luminary: lawyer, activist, poet, and priest who transformed our world.”

Despite having completely re-contextualized one of the most influential black women of our time as a “non-binary person”, there was a strikingly short segment in the film that fleshed out their justifications for doing so. Instead, they interviewed a couple of well-known, black, trans-identifying people, and asked them to share their impressions and interpretations of Pauli Murray’s struggles with gender and sexuality.

This segment of the film begins with the VoiceOver of Raquel Willis, a black trans-woman writer, saying “These experiences have always existed” over a dreamily slow photo sequence of Pauli Murray wearing boys’ clothing in her teen years.

Ah, yes. Sounds a lot like a revised mantra of “trans people have always existed”. Unfortunately, Willis’s vague, yet romantic statement about Murray neglects the fact that these experiences have not always existed.

Eurocentric gender stereotypes that lead sexually non-conforming people to feel socially ostracized enough to desperately seek relief through Western medical experimentation—particularly as a black homosexual woman in the Jim Crow South—did not always exist, my friend.

Pauli’s experiences are entirely a response to a very specific modern social construction, and a deeply broken system.

The film goes on to highlight the voice of Dolores Chandler, a black trans-man, and the coordinator of the Pauli Murray Center.

Dolores openly acknowledges that those who were closest to Pauli Murray, including friends and family, refer to Murray using “feminine” pronouns of she/her, and expresses hope that in the future, more people will refer to her with “gender neutral” pronouns.

Aside from going above and beyond the knowledge of Murray’s loved ones, I find it greatly troubling that Dolores references she/her pronouns as being “feminine” instead of “female”.

When reading between the lines, I actually think that this perspective is one root of the problem—implying that female=feminine, and inadvertently ousting masculine, gender-nonconforming women from the “she/her” category by virtue of them not being feminine.

In reality, womanhood and she/her pronouns are for every woman. Pronouns, in their original form and common usage, are not based on feelings, personality, or identity. They are linguistic tools to refer to one’s biological sex within the world languages that use them, including English. It has nothing to do with masculinity or femininity.

But by adopting this ideology that she/her means “feminine”, it reinforces the paradigm that caused Pauli Murray so much pain and anguish in being who she was. There was no language, concept, or space for being a masculine woman, and that void was deeply felt.

Dolores also talked about identifying with Pauli’s turmoil about her gender, and goes on to state,

“We’ve been taught to believe that people like us don’t exist. So when I came to know and learn about Pauli Murray, I was so amazed and wanted to like hold it so tightly. And also I was angry…I was so angry, that I felt I had in some ways been robbed of a part of my history.”

Hmmm. Very interesting. With Dolores being the Coordinator of the Pauli Murray Center, and having such a personal, deeply emotional investment in the idea of Pauli Murray being transgender—seemingly as a projection of personal issues—and noting the fact that there is such shallow history on trans-men—might we have a clue as to why The Pauli Murray Center has chosen to take the official stance that it has?

I think we’re onto something here.

This brings me to my next point. Why is all of this happening?

Why Are Women Like Pauli Revised in History as Queer and Trans?

Within the past decade, we’ve seen a sharp rise in the number of people who identify as queer, transgender, and non-binary, within the Western World. This number has particularly spiked amongst young girls and women who opt to identify out of womanhood and medically transition to reflect their newfound identities as men.

Not only has it become a trend, but this cultural boom has also resulted in certain ideologies about gender being pushed into all spheres of public and private life.

Female spaces of all kinds are now deemed as hallmarks of bigotry if they do not offer a warm welcome to biological males. Pronouns are now analogous to personality traits.

Whereas asking for someone’s preferred pronouns was, for a brief period, a social practice exclusive to “LGBT” community circles, it’s now mandated amongst straight, gender-conforming people as a ritual within various corporate workplaces, organizations, and social settings. I must note, that this transition happened at a disorientingly rapid pace.

There is immense pressure on the average person to acknowledge and center “Trans” in their everyday life, whether it’s through the flags they fly on their front lawn, the people they date, the language they use to describe their bodies and experiences, and the books they read. There’s no mistake that there has been a massive cultural shift. Why is this shift happening? Just follow the money, and you’ll find out. But that’s another ball of wax.

Within this rapid shift, there is a scramble to legitimize transgenderism as a distinctly marginalized group of humanity that is comparable to racial minorities, women, and LGB people. Thus, trans-activism has brought forth several mantras, to solidify itself.

One of those mantras is, “Trans People Have Always Existed.”

The best way to prove that something has always existed is by going back into history and collecting receipts to prove it.

Unfortunately, this is where receipts tend to fall short.

Although ‘gender non-conforming’ and homosexual people have certainly always existed, the concept of transgenderism is still relatively new, and very much tied to the Western world.

After all, trans is an identity tied to a specific philosophy on gender, which relies heavily on Western gender stereotypes, language, cultural norms, and even medical practices.

What’s more, most of the richly documented history we do have about Trans people, is mostly about biological males, or trans-women, and the bulk of it is dated within the last 100 years or so, only confirming that it is a relatively recent phenomenon.

There are very few historical cases of women “transitioning” to openly identify and appear male, for “gender-affirming” purposes. There were, however, a lot more women who posed as males to gain professional opportunity, or for survival, such as wartime cross-dressers. A case could be made that some transsexuals were stealthy, and that we may never know who was who.

But regardless, I do think it’s important to note that the concept of transgenderism that we have today and how it functions, is very distinct to our place and time, and it can’t be retroactively applied to the past, or non-Western cultures without having to create a high level of distortion.

So what do people do in this case? If you have no Trans History, there’s no other choice but to create one. And that’s what they’ve done.

One of the most insidious ways this can be achieved is by changing the language we use to meaningfully describe ourselves.

Changing language is often the first and easiest step in re-contextualizing old language and events to form new narratives.

A very prominent example of this is how mainstream media has re-branded several lesbian, gay, and bisexual historical figures as “queer”.

We can see this phenomenon with the queering of lesbian icons like Audre Lorde, Stormé Delarverie, Angela Davis, and several others.

In Pauli Murray’s case, some biographers have re-contextualized her usage of the word queer, sourcing her letter to her friend Helene, where she states how grateful she is to find a space where their “queerness” is considered normal.

It’s important to note that in Pauli Murray’s day, the word queer was either used as a homophobic slur, or it simply referred to something or someone odd or unusual. The latter definition makes more sense in the context of Pauli’s letter, especially given that she never explicitly labeled her sexuality, beyond describing it as homosexual. But if one researches Pauli Murray, we can now find most sources labeling her as Queer, or insinuating that this is how she identified herself.

The problem with the modern usage of “Queer” is that it doesn’t really mean anything. Unlike other words that have changed over the years to mean essentially the same thing, such as “Negro” to “Black”…the term Queer doesn’t hold any solid ground.

In the early 2000s, there was a cultural wave for same-sex attracted people to reclaim the term “queer” and reduce its power as a homophobic slur. So, for a couple of decades, “Queer” was used amongst LGB circles as an umbrella term, to describe a same-sex attracted person: either a homosexual or bisexual.

But much like “Trans”, the word Queer has mutated into something that anyone can identify into, if they so choose. Plenty of straight people have appropriated the word, and now identify as Queer because they feel like they are counter-culture in one way or another.

The word Queer is now used either on its own, or alongside other trans identities as a “catch-all” identity that doesn’t require someone to meaningfully describe themselves or their sexual orientation using language that refers to biological sex.

Queer means nothing and everything at the same time, and it doesn’t say anything in particular about one’s social positioning, sexual orientation, or lived experience. For this reason, I believe that rebranding homosexual and bisexual historical figures as “Queer” is also a form of erasure.

Although Pauli Murray has received due recognition in her time, she was not a very popular historical figure, until scholars dug her up within the last few years, and found a way to rebrand her as transgender.

For some people, Pauli’s numerous accomplishments and legacy are not as valuable as a black woman as it is as a man or transgender person. I think this says a lot about our current times, and how the Trans movement views and devalues women.

Final Thoughts

In researching for this essay, I saw a lot of parallels from Pauli’s time until now. Times have certainly changed, and Pauli’s courageous life played a major role in creating the freedoms and rights we enjoy to this day. But when looking back on history, especially on Pauli Murray’s early-life journey, I also see that some things have remained the same, and perhaps even regressed.

I still see people struggling deeply in their relationship with their sexuality and learning to love themselves as they are. But I also increasingly see gender-nonconforming women being socially pressured to transition to take hormones, or being assumed to be transgender. We still live in a world that leads women to struggle in a lot of the same ways Pauli Murray did.

After the feminist movement and boom of lesbian culture in the 80s, the trans movement has largely suppressed female voices through erasure, as well as a push to change our language and boundaries in the name of inclusivity. There is still very little visibility or community support for women who walk through life in Pauli Murray’s image. These pressures create a world that discourages women from becoming their full selves, and this needs to change.

The definition of a woman is an adult human female.

Women are women, no matter how we dress, who we love, how we walk or talk, or what we like to do in our spare time. I envision a world that allows non-conforming people to feel that we have a place on this planet, without having to stuff ourselves into a box we will never fit.

Real inclusivity doesn’t demand us to change the definition of Man or Woman, or to change certain people to fit inside of it…it simply accepts and embraces those who are already there.

This is the best clarification of the historical record of Pauli Murray that I have seen, by far. I really appreciate your deep dive and challenge of the back-projected mythologization which ignores the climate of homophobia she grappled with. Your points about the disrespect to her own self-expression over the course of her life are well-taken, and the first time I have seen the suggestion that, if that trans interpretation was to be taken seriously, then she would be detran. Great work.

Wow. Stunning piece of writing. I was recommended to read it on spinster.xyz

As a 64 year old Tomboy who went through gender-distress (and extensive bullying) as a child and teenager, I deeply sympathize with this amazing lady.

I'm glad for her that, like me, she lived before this insane modern craze to delete masculine-appearing women from society. We're here, we're proud, and we're activists!