Believing in Myself Amidst the Odds and Haters.

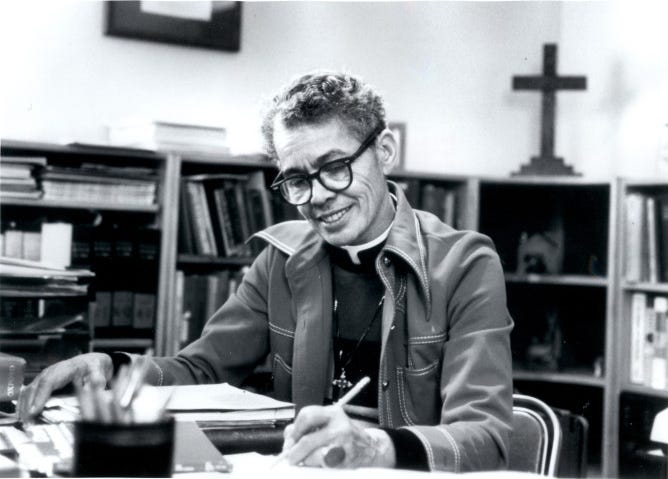

A few months ago, I recognized that academia and the mainstream media had begun to dig up the histories of some prominent black lesbians in civil rights history, and posthumously refer to them as men, transgender, and non-binary people.

Being a scholar of black women’s history myself, I’m very protective of our stories. The idea that our valuable contributions, experiences, and works as black women were literally being erased by the trans movement was abominable, and I couldn’t pass it by. There was one figure who stood out to me in particular, and I wanted to know what exactly was about her story that people were taking out of context.

So, I decided to do some research at the Harvard University Schlesinger Library, where her archives were stored, so I could craft a proper response to what I was witnessing in our culture.

At the time I am writing this, I am in Cambridge, MA and I just finished three days of research at Harvard University. I now have everything I need to write my piece. But the journey here was not easy—especially on an emotional level.

I want to talk about my experience requesting financial support for this research project, some unexpected ways I was let down and blocked from a valuable opportunity to do so by someone who I thought truly supported me, how I found my way, and how these experiences have helped me strengthened my belief in myself.

When I first decided to take on this project back last Fall, I was researching grants that could support me in my work as an Artist, and as an Entrepreneur. I listed all sorts of grants to apply to in 2024—mostly unrestricted funds, so that I could just use the money for whatever I need.

I knew that this project I had in mind was controversial, and I thought it would be nearly impossible to obtain a grant from any major Arts or Academic Institution to fund the research I was doing.

But I still looked, and to my pleasant surprise, I found that the Schlesinger Library for Women’s History, was offering $3,000 grants to independent scholars and researchers who are researching materials that can only be found at their library.

The application was stunningly simple—only a C.V. and short project proposal was needed.

However, they did require a recommendation letter. Ugh.

And, they only accepted applicants who had A PhD or equivalent in writing and research experience. Ugh.

Yet, I was encouraged. I saw a window of possibility.

I don’t have a PhD. but I knew that my film was definitely equivalent in research experience. For me, at least. And, for some. I didn’t know what the hoity-toity Harvard Schlesinger Library would think, but they do have my film in their archives.

So there was that.

I figured, if I worded my proposal properly yet vaguely enough, I could stimulate their intellectual interest without giving away the fact that this entire project is discrediting trans ideology. Plus, this a Women’s History Library. Maybe they would be on my side!

And then finally. For the recommendation letter, there was only one person I had in mind to ask—and she was my only real bet.

I chose someone who was familiar with my gender-critical work, highly-credentialed, and who a recent history of supporting and collaborating with me.

But I wanted to make sure I fleshed out my project and wrote the entire proposal first, so that she could know exactly what she was signing off on.

Shortly after I placed this grant on my to-do list, so began my hurdles. I fell into a homeless crisis scare not less than one month later, which completely threw me into survival mode.

That scare has not completely resolved, but it has momentarily calmed down enough that I’m able to pace my efforts and refocus my energies on what is most important to me, which is planning for my financial future. This grant was a seed planted for that future.

In writing this grant, I was not only thinking about this project, which I presumed would not be too costly, and which I was committed to find the resources to do, hell or high water…

I was also thinking that since the grant pays for living expenses while doing the research, I can have some financial cushioning if the rug gets pulled out from underneath my feet again for housing. It would be an extra resource in my back pocket.

Most importantly, I knew that I deserve the money, and the money is there, so why not take it?

This is what rich, well-connected white people do all the time! They get massive grants, funding, and support for their Art and Intellectual pursuits, and they live comfortably off more than they really need.

But somewhere along the line, my confidence in myself started to shake.

By the beginning of January, I had convinced myself that my project was too controversial, too out of the box, and that, after all, I am not a PhD. so why should I even apply?

“They will never accept me.” I thought. This is Harvard University! I am under pressure. This is a waste of time. I need to focus on what will bring me money right now.

I abandoned the entire grant application.

One week before the grant application was due, I received an automated email from the Harvard Grants administration, reminding me to complete my application before the deadline.

I don’t know what it was about that email that changed my mind, but I knew that I only had one shot, and I didn’t want to let it pass me by.

I was very busy at the time with other work, but I decided that I would give the grant application my best shot—under one condition.

I wanted to know if I was even qualified to apply.

I emailed the grand administrator, shared information about my film, and asked if I would be considered to have a “PHD equivalent”. I received a prompt response:

“Hello Nevline, Thank you for touching base. Yes, we would absolutely consider your professional experience/expertise to be on par with a doctoral degree, so you should proceed with applying for the Research Support Grant.”

I was pleasantly surprised, and encouraged once again. That was all the confirmation I needed. Harvard thinks my film is equivalent to a PhD. I took 3 days out of my busy work schedule and completely devoted them to writing my grant. One day for each part: My CV, my Proposal, and the Recommendation Letter.

The first afternoon, I worked on my CV.

I crafted an Artist CV that was succinct, and which highlighted all the points that would impress them. “My film has screened at all the top Universities in the world,” I said.

Wait. Is this true? Can I actually say this? I actually googled a list of all the top Universities in the world, just to be sure. Yup. It is true. Then I listed a few of them out in order:

2020-Harvard University

2018-Oxford University

2017-Yale University.

“Wow. If this is true, why do I only have $100 in my checking account right now?”

The amount in my checking account changed a couple of days later, when another University bought my film.

But it was a noteworthy thought that crossed my mind. That I don’t always feel like the success I’ve reached, because it hasn’t manifested materially in a specific type of way at this time.

That doesn’t mean I shouldn’t own it.

Then, came the proposal. The proposal was the hardest part. I had to find a way to delicately explain my intentions for the project, revealing how unique and cutting-edge it is, without using some language I would normally use when referencing topics like this, such as “trans ideology” and “gender ideology”.

I sweated bullets writing the proposal for this very reason. But in the end, my proposal was on-point, and I knew that anyone worth their salt would fund me.

Finally, came the recommendation letter.

The negligence and betrayal I experienced from here, was very unexpected.

And this is ultimately what led to the demise of my application, and quite a bit of heartache.